Tuesday, November 23, 2010

Giving Thanks: Serving Thistle

The more you try, try to organize, the more that you come up with problems. But eventually, you can find a path. Find that path. There exists a path. A repetitious cycle running, running through your head. And you can sing it, or you can write it, or you can fight it until it’s dead. But death ain’t so bad sometimes, cuz birth happens too.

Birth happens. Sh*t happens. Death happens.

Jazz. It happens. Moments of brilliant strokes. Spontaneous art occurring at the point of combustion. One man’s conception is recontact. Giant Steps. Constant yearn, burn, want of the path. Wearing out the soles of their shoes, their souls, walking the path. A religious pilgrimage to the Sound.

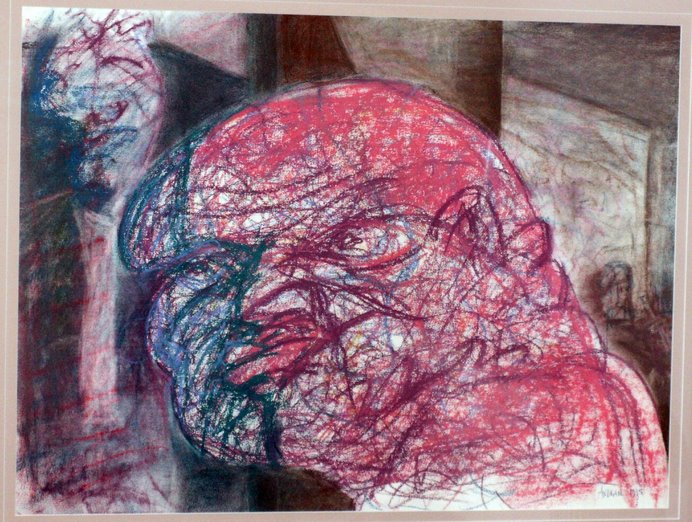

Art. Many forms, many shapes. Many ways to approach it’s formation, it’s conception, it’s organization. One man’s way is to liberate the masterpiece that already exists deep within the block of marble. Not to organize the block to a pre-conceived notion of beauty in his head, but to illicit and liberate as the beauty makes itself evident to him. His job is to ease its passage into existence. The great Life/Death transcendence into existence. Creation.

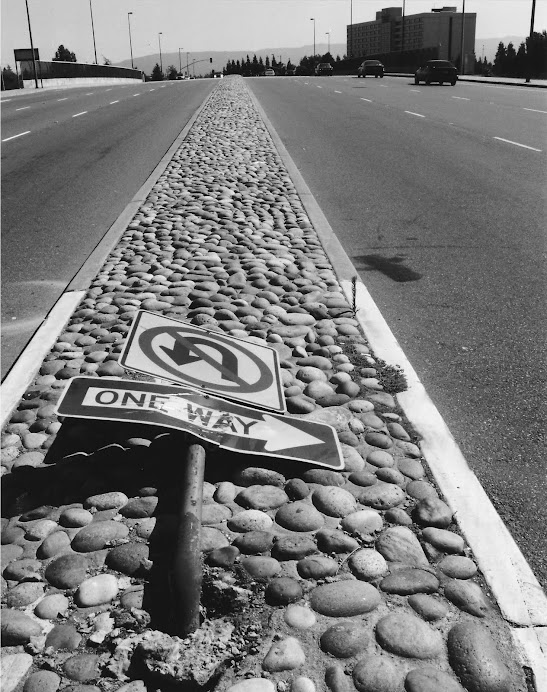

Thistle once wrote a poem about the human need to organize. He wrote it on a credit card receipt as he was trying to drive. Steadying the keel with one hand, creating with the other. Many other drivers sounded their distracting disapproval of his somewhat meanderous driving. But he kept going, down the road, on with his writing. Following his path.

Fiction. It happens. People don’t believe it like they do their reality, but trust me. It happens. Sometimes an author writes of a completely unfounded, unbelievable, and very fictional experience, and the next day, it happens. Cosmic convergence. Extremely interesting.

Sometimes an artist can sit down in front of a blank sheet of paper, take a pen, and just start openly scribbling and fervently scratching ink all over the page, and after some time, a window is opened up to creation, and an image is brought to life. It happens. Very Interesting.

And sometimes a saxophone player can pick up his horn, prepare his lips, close his eyes, and blow. And what you hear is unrelenting, unprecedented, and unique beauty. Created at the moment, experienced within its moment of conception. Again. Interesting.

Is this a place where God resides? Is he present in the questing practices of the artist? Is he the One, the awareness, the beauty that the artist liberates from the marble, from the blank page, from the mind?

Man. Where do I start?

Nevermind that. Just talk.

Major breakthroughs tonight. I realized that I still can’t really type, but I also realized that that will come, is a transient reality. That I can push through it and recreate beyond it, in spite of it. The skill will come. With practice. Much practice.

Like Coltrane. You actually think that he just picked up the horn one day, set his fingers on the keys, and just blew out a solo faster than a train through Detroit?

No. I am pushin. Pushin. Pushin forward back.

The Muse. The Music. It intertwines. The infinity knot. A crossover. Cycllical. circular. Tape loop. Cliche. “Oh, that’s all been said before.” Yes, but for a reason.

Truth. Get to know it. Pass it on.

Coltrane’s Sound. An album I own. A path that I research. A sound that inspires a visual imagery, a colored picture in my mind. I look inside and see what I’m hearing. What’s John saying? Can words keep up?

Sound is fast. Express. Much more efficient. You hear several sounds at once. Soundscapes. Landscapes. You can only hear one word at a time. And understand. Understanding is slow. Takes more time. If you try to listen to more than one word at a time, you can get confused really easily. But harmony is sweet.

Thanks to my friend, a new acquaintance in my life, I have found a path that connects a segment of my improvisational writings to the core of my being, the core of my projects as a writer. It’s within the cover of Coltrane’s Sound.

“When Ernest Hemingway died, Nelson Algren in a moving tribute from one great novelist to another assessed Hemingway’s importance, saying, ‘No American writer since Walt Whitman has assumed such risks in forging a style…they were the kind of chances by which, should they fail, the taker fails alone; yet, should they succeed, succeed for everyone.’

“That is–from where I stand–a perfect description of precisely what is going on with the tenor saxophonist John Coltrane.

“Coltrane personifies the young jazz musician who, in searching for personal style, in striving to establish his art as valid and individual and real, takes chances in forging a style which, by definition, challenges the form of tradition while remaining loyal to its essence, and assaults the conventional and the orthodox.

“Jazz musicians like Coltrane are linked inexorably with those creative artists such as Joseph Heller, Ken Kesey, Lenny Bruce, and others who are searching for what Kesey (in a recent issue of Genesis West) referred to as ‘a new way to look at the world, an attempt to locate a better reality.’

“And it ought to be noted about such jazzmen that they not only represent the improvisatory aspect of our society, but by the very nature of what they do, take more chances, even, than Hemingway. For the jazz musician such as John Coltrane is improvising, making it up right now, creating, instant art in the supermarket of the jazz club, which is like writing poetry in the men’s room at Grand Central Station.

“And they perform this improvisation without the chance of revision, with the knowledge beforehand that what comes out may be good or may be bad; it depends. But in any case they can’t change it, it must rest where it is and be judged as it came out.

“In the process of this striving, a creative jazzman such as John Coltrane may very well annoy and antagonize in exactly the same way as Joyce and Stravinsky and Bartol, in their times, have annoyed and antagonized.

“Coltrane plays long solos in which he frequently eschews the melody of the tune and embarks on a long volatile series of flagging improvisations. He plays with a hard tone in a rushing, dynamically aggressive style that sounds as if he might be angry.

“For this he has been criticized as ‘an angry young tenor.’ Coltrane’s reply is interesting. ‘The only one I’m angry at is myself,’ he says, ‘when I don’t make what I’m trying to play.’

“What is he trying to do?” is the question frequently asked about Coltrane and constantly hurled at musicians and critics by irritated listeners who feel their good will toward jazz frustrated by what they find to be the inexplicability of Coltrane’s playing.

“He has a simple answer. ‘The main thing a musician would like to do is to give a picture to the listener of the many wonderful things he knows of and senses in the universe.’

“Once he remarked on his fascination with harmony. ‘When I was with Miles, I didn’t have anything to think about but myself, so I stayed at the piano and chords! chords! chords! I ended up playing them on my horn!’

“From his association with some of the most famous and most individual performers in jazz, such as Miles and Monk and Dizzy, Coltrane finds a similarity underlying their work. There’s just ‘one thing…remains constant.’ he says. ‘That’s the tension of it, that electricity, that kind of feeling. No matter where it happens, you get that feeling and you know. It’s a happy feelin,’ he adds.

“Coltrane, a mild, soft spoken and highly introspective man, says of his own music, ‘Sometimes I let technical things surround me so often and so much that I kind of lose sight…basically all I want to do would be to play music that would make people happy.’

“The long solos, the unorthodox ‘cries’ and the sheets of sound, the hard tone, the swift changes of mood from the lyric to the turbulent urgency of his modal improvisations, indicate a restless nature. And Coltrane is still unsatisfied with his own playing. He is searching. ‘I don’t know what I’m looking for,’ he has said, ‘something that hasn’t been played before. I don’t know what it is. I know I’ll have that feeling when I get it and I’ll just keep on searching.’

“There’s a story told by Cannonball Adderley who worked with Coltrane in the Miles Davis group. ‘Once in a while,’ Cannonball says, ‘Miles might say, ‘Why you play so long, man?’ and John would say, ‘It took that long to get it all in.’

That’s a pretty good summary of what motivates and inspires and directs the life of this jazz man. His music is all-encompassing; his vision of life so packed, that he does, indeed, sometimes have trouble ‘getting it all in.”

Ralph J. Gleason wrote that. There’s a little more, but I don’t think I need it repeated here.

Just extra notes.

So. The path. Yeah– find that path. Improvise and explore and discover the way. I hear it, see it, attempt to write it. Still, I need practice. I pound and pound as if a blacksmith, shaping my thoughts into a functional machine. But it takes more than brute strength. Afterall, I’m not making horseshoes. It takes finesse. Patience. Mindfulness. Perseverance. Open-mindfulness. Resolve.

My path crossed that Of John Coltrane’s tonight. I also ran into Arrested Devlelopment. Fishing for religion and just preaching a beautiful message. What a good. Plenty more quotes to come.

Made me think. I have mentioned Sinead O’Connor in past writings. Why did I connect with her so? I think that I heard her where a lot of others did not. Maybe her message was a little too ambiguous and easily misinterpreted, but I felt that at the base of it was not hatred, but love. A similar message to Speech’s. There are lies that we must push through, dismantle, tear up on national television. The better reality is there– it has to exist, or how could we think of it? If it doesn’t exist, then what is it?

Do you follow? The path leads to science. Michael Chrichton. Chaos Theory. The stability of science– it’s predominance in our time. Science as religion. Science as a lacking description of reality. Science as myth. Robert Pirsig’s scientific “ghosts.”

The scientific orientation of the twentieth century mind creates our reality. What doesn’t connect with the theory is said to be invalid, wrong, unreal, etc. So these things don’t exist? Even though by the powers of our observation, the same powers we trust in formulating our scientific theories, we are able to sense and feel and experience things unexplainable by scientific postulation– is this a limitation of the observed event, or the observer/observer’s tools?

It’s all bottled up in the stew. Somewhere in there, Thistle’s digging in the dirt, throwing up little shards of glass and petrified wood, trying to communicate his story.

It is obvious to me that Thistle exists. If only in my mind, as a thought, He still exists. I flesh him out more and more as I write and talk about him. His dream is to bridge the gap between scientifically defined non-existence and existence. He’s played the gig of predicting the future. He’s looked through walls in bus stations, restaurants, theaters. He looked through walls put up by people to protect them from things. He’s seen through walls constructed by theory. He’s watched infinity pass by hundreds of times. He imagined living in my body. He’s imagined being one with me and sitting down at the computer and writing out his life’s story. But he can’t seem to bridge the gap between the stew and the Elsewhere. He can’t pass through the cauldron intact.

He exists as a thought, swimming in the stew of the unconscious, or the sub-conscious. He exists as much as an invention exists in the mind of the inventor before he materializes it and creates it from the raw materials at his disposal. And the cauldron which holds the stew, keeps the stew from running all over the place, holds the stew in place, static, restricts him from moving outside of the stew, the subconscious, into the Elsewhere, the open air of the cabin, out into the fire which burns below, cooking the stew. The cook does not stop to think of Thistle as he stirs the stew every hour. Even when Thistle imagines himself crawling up the cook’s spoon, peeling back the food stained cuff of the sleeve and biting the stirring cook’s wrist, the cook goes on, not noticing.

But the writer notices. Somehow, we are projected to the same space. We see through enough of the same walls and connect on another plane.

It all starts with a belief. I believe in Thistle Penn, and he is born.

Voila. Bon appetit.

Dinner is served.

Turkey anyone? And with your mashed potatoes– some philosophy, perhaps?

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

2 comments:

This is too deep for me on my first read. I will have to read it again and again, each time gleening a little more from it.

Keep writing, Mike...you are really good at it and Thistle and his story will eventually get out through you. Love you lots!!!!

I'm not sure if this was intended but your idea of improvisational writing describes a lot of what bloggers do. But as a blogger I cannot accept that as describing me personally because Coltrane practiced 14 hours a day virtually everyday before he improvised to his audience. I'm unlikely to do that. Like Gerri I'll have to come back later to receive everything you're put in this post; I'm particularly interested in the pure subjectivity of reality, which you imply -- IMO the only kind with meaning.

Post a Comment